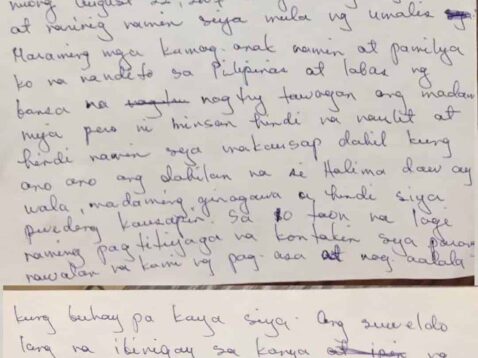

The only way her family could contact her was by calling her employers’ house phone. Halima’s husband, Ginaid Kasem, sacrificed a great deal in trying to contact his wife. As there was no electricity in his village, he had to travel miles to the closest town to call Halima from a pay phone. With the little money he had, he would call his wife’s employers and ask to speak to her. Each time, Ibtissam Alsaadi would either keep him on hold until his phone card ran out, or tell him that Halima was unavailable.

“Sometimes they would say ‘your wife is coming’, and at other times they would answer, but not say anything,” says Ginaid. Every single time, his money would run out without him having spoken to his wife, and he would have to make the long trek home.

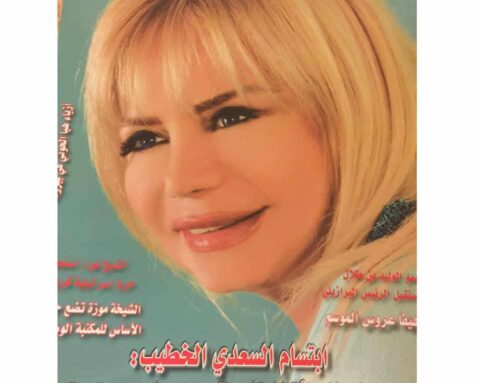

Halima says she spent all day, every day, cleaning up after Ibtissam Alsaadi and her family, and in return being physically and verbally abused by them. Halima was on call 24/7, she didn’t get any time off, and she suffered profound physical abuse at the hands of Ibtissam Alsaadi and her family. When she explains, it’s clear she is visibly distressed at the memory, and tears roll down her face: “My madam, for the smallest, tiniest mistake would slap me.” She points out the scars from where her employer scratched her neck with her nails.

Another time, Ibtissam Alsaadi allegedly struck Halima with a mop while Halima was cleaning the balcony. Halima’s legs are covered in scars. She recounts how once she was making coffee and she spilled some on the stove. Ibtissam told her: “Halima, why didn’t you see this? Where is your brain?” She then allegedly threw the boiling coffee over Halima, which left extensive scars on her legs.

Almost all of Halima’s nails are brown and black, badly damaged from cleaning. “They didn’t let me use gloves,” she says. “The madam told me, no, you don’t need to have gloves, because you are just a maid here.” Halima adds that Ibtissam Alsaadi would frequently threaten to kill her if she didn’t complete her tasks quickly enough.

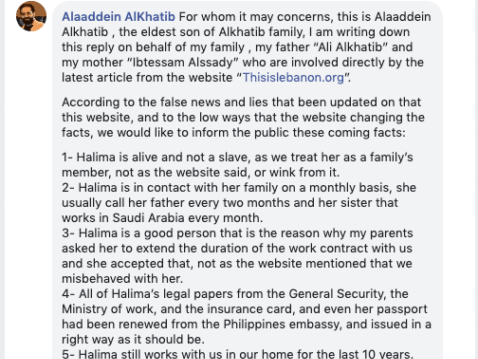

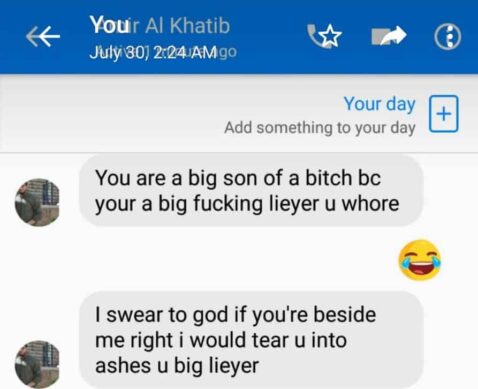

Halima was also abused by other family members. She recounts how one of the sons, Alaaddein (Alaa), would punch her. “When Alaa ordered me to do something, he expected it to be done instantly. And if I wasn’t fast enough, he punched me and slapped me.” She alleges that once he hit her with a large piece of wood and fractured her right arm. “It got very big and swollen. I couldn’t move it. They put something on it.” [referring to a cast].

Once when Alaa was hitting Halima, Ibtissam Alsaadi’s husband Ali tried to help her. He said: “Alaa, don’t do that because Halima is like family,” explains Halima. Then Alaa asked his father: “Why? Is she your daughter? Is she family?” Ali AlKhatib told his son to leave Halima alone, and that he felt sorry for her. But the abuse continued.

In our documentary filmed in her hometown, Halima explains how her thoughts turned to dying as a means of getting out of the household: “I wanted to escape, but how could I? They always locked me in the house. I thought of committing suicide, but then I thought of my children,” she says whilst crying. Even when Halima washed the family’s cars outside on the street, her employer would watch her from a balcony above to ensure she did not run away.